What Reparations Can Look Like

The Reparations Task Force of Maryland’s Episcopal Church makes its first grants.

Many people in the United States wonder, why reparations? I did not own slaves, and maybe my family didn’t own slaves, and I love everyone. Today is part of that answer. — Bishop Eugene Taylor Sutton

At Hard Histories, our work focuses on recovering those facets of our past at Johns Hopkins that are difficult to admit, forgotten by neglect and by design, and suppressed in the interest of burnishing our image. We term this work reckoning, aiming to be part of efforts that looks unflinchingly at where we’ve come from and how we’ve arrived here.

Many of you have asked us what comes next: Shouldn’t reconciliation, repair, and reparations follow on the heels of what we learn about how our present was built upon racism and the resulting injustices. While our work doesn’t expressly craft those solutions, we know that our community needs to meaningfully act in the interest of a future that is equitable, transformative, and just.

We’ve been following the reparations project developed by the Maryland Diocese of the Episcopal Church. And just two weeks ago, Bishop Eugene Taylor Sutton announced the first cash awards (six of them at $30,000 each) being paid to “nonprofits,” church-affiliated initiatives and youth centers” committed to the well-being of Black children and their families.

Reactions to announcement of the grants have been varied, with some praising the church for taking this substantive step forward with high expectations for the justice that a $1 million fund can make possible. Others note that the church began this work years ago now, and suggest that these grants are too little and perhaps too late. (Yes, we do read the comment section!)

Whatever its merits, the approach of Maryland’s Episcopal Church provides one example of how institutions can learn their own history and then act to atone for it. Other examples include the plan for truth and reconciliation at Georgetown University and Evanston, Illinois’s $10 million fund which aims to make reparations for the city’s historic housing discrimination. Reparations for slavery and discrimination are the subject of a global discussion. Among the most recent advocates to place the issue on the world stage was the New York Times’ Nikole Hannah-Jones, who spoke to the United Nation’s General Assembly on reparations for slavery this spring.

Calls for reparations date at least as far back as the 1890s in the United States when organizations like the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association of the United States of America, led by Callie House, organized to win compensation and support for aging and infirmed former slaves, a demand for recognition of their long-uncompensated labor. The movement failed, or better put it was crushed by federal officials who prosecuted leaders arguing that soliciting support for such pensions was a form of fraud. Reparations for slavery in the 1890s was unthinkable in the minds of US Postal authorities who looked to suppress the movement by barring its use of the public postal system to raise funds and support.

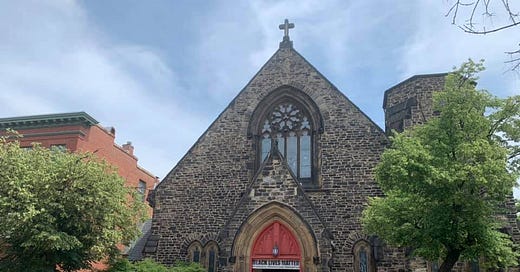

Today, calls for reparations still generate debate and opposition. And still, we can point to concrete examples in which communities have reckoned with the past and then acted to repar it. Consider, close to home, Baltimore’s Memorial Espisopal Church in the Bolton Hill neighborhood which has engaged, since 2017, in a reckoning with its origins as a memorial to slaveholders. You can read more about Memorial Episcopal and its work here.

At Hard Histories, we both recognize the enormity of the work still to be done here at Johns Hopkins. At the same time, we aknowledge how our work is a small part of the grander project of reckoning with the roots of many Baltimore institutions, incuding some of its Episcopal Churches, in enslavement. We are humbled and inspired all at once.

— MSJ

P.S. Our Substack in on a summer schedule. Please stay tuned for our occasional posts here!

As a I reflect on this article and the few institutions who are involved in substantive repair for past harms. I am encouraged. There will always be much to do, but I believe the role of historians in this work serves to point institutions in the right direction. Thank you!