A New Chapter in the Life of Mr. Johns Hopkins

An 1850 Petition Reveals How Domestic Slaveholding, a Burgeoning Free Black Community, and Benevolence Were Intertwined in Baltimore City

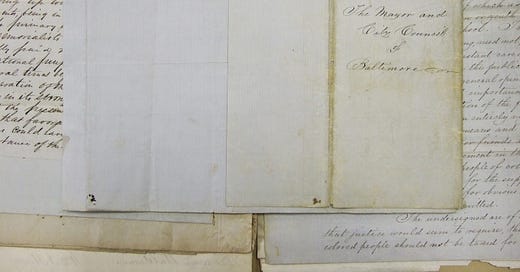

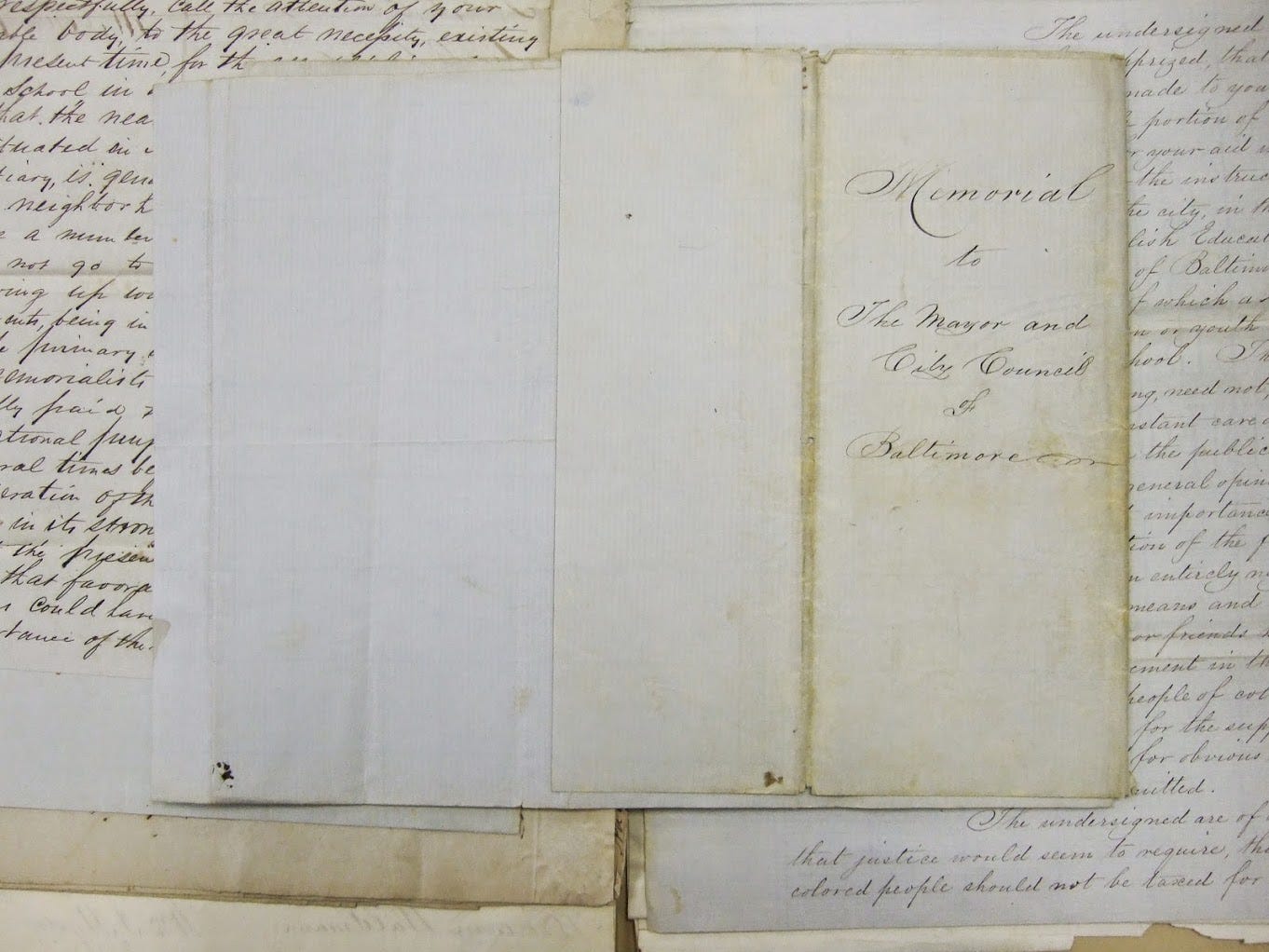

The Hard Histories at Hopkins Lab, in collaboration with our colleagues at Hopkins Retrospective, have spent this fall investigating a newly surfaced document. The details of an 1850 petition — “Memorial to the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore” — has opened a new window onto how slavery, free Black people, and benevolence mixed in 19th century Baltimore. Finding the signature of Mr. Johns Hopkins affixed there, among those of nearly 120 of his peers, is allowing us to write a new chapter in the life story of our founder and namesake.1

In 1850, the city’s leading merchants, bankers, ministers, politicians and more — among them enslavers — put forward a request to city officials, one that sought “the establishment of schools for the instruction of the free colored children of the city in the elementary branches of an English Education.” The petition was put forward only after decades during which the city’s Black religious and civic leaders had independently raised funds and stood up schools for Black children, who had been long excluded from public education. Despite its backing by distinguished leaders, the petition failed. Baltimore City declined to support schooling for Black children until after the Civil War.

Over the coming weeks, the Hard Histories Substack will explore the insights earned through careful study of the petition. Still, to call the 1850 petition a new discovery might be misleading. It was serendipity the brought the petition to the attention of the lab. This might surprise some of our followers. Still, the experienced researchers among us can affirm that even as they employ established methods, systematic investigation, and insights derived from related studies, it is also true that serendipity or good luck in making an unexpected but welcome discovery can play a critical role in moving an inquiry forward.

Historian Hilary Moss, in her 2009 book Schooling Citizens: The Struggle for African American Education in Antebellum America, has conducted the most careful research to-date into the 1850 petition and the broader struggles over Black children and public education in Baltimore. Dr. Moss explains that Black education was not only legal in Baltimore and Maryland, though generally outlawed in other slaveholding states. Raced-based exclusion led Black Baltimoreans to operate their own schools, many associated with well-established Black churches. The city’s white leadership not only tolerated such schools, they even encouraged them in a view that mixed benevolence with self-interest. The city’s elite were eager for schools that prepared Black children to be able workers with at least a rudimentary capacity to read and calculate.2

The terms of the 1850 petition reflected these very interests of white Baltimoreans: “The true interest of the white population, as well as of the colored, will be promoted by the instruction of the children of the latter, in such elements of learning as may prepare them to fill, with usefulness and respectability, those humble stations in the community to which they are confined by the necessities of their condition.” Black children, in this vision, were suited to an education that prepared them for “humble” work lives as manual and domestic laborers. At the same time, the petition called for “justice”: “The colored people should not be taxed for the education of the children of others, while their own children are excluded from all opportunities of instruction.”

This latter concern for fairness when it came to taxes was adopted by white petitioners who borrowed from petitions presented to the Mayor and City Council by Black Baltimoreans in the years before 1850. These activists had long insisted that it was unfair that they were taxed to support the city’s public schools while their children were barred from attending them. If they were to be taxed, they argued, public funds should be used to support schooling for Black children.3 In fact, in 1850 city officials were presented with two petitions. The first came from Black leaders who explained that, while Black residents independently supported a school for eighty children, that arrangement was financially unsustainable. Their solution? Absent establishing Black public schools, the city should return their tax payments, allowing the funds to be applied to their struggling classrooms. Only then did a subsequent petition, signed by Mr. Hopkins and his more than 100 elite peers, follow.

We’ll close by returning to the element of serendipity that let us connect the history of the 1850 petition to Mr. Hopkins. Hard Histories director, Martha Jones, had first encountered the original petition in 2014, more than a decade ago, while researching her book, Birthright Citizens at the Baltimore City Archives. She left that visit with dozens of photographic images that included the two page document and its long signature page. Only when she returned to that same petition in 2024 did she recognize one important signatory: Johns Hopkins. During first encounter with that petition Mr. Hopkins was not the subject of her research. Having another look ten years later, and with the work of Hard Histories at Hopkins in mind, Mr. Hopkins’s signature nearly jumped off the page. Serendipity.

Follow us in the coming weeks as Hard Histories lab member Matthew Palmer and Dr. Monica Blair, formerly the Hopkins Retrospective Historian and Education Coordinator, take a deep dive into the 1850 petition and its signatories.

— MSJ

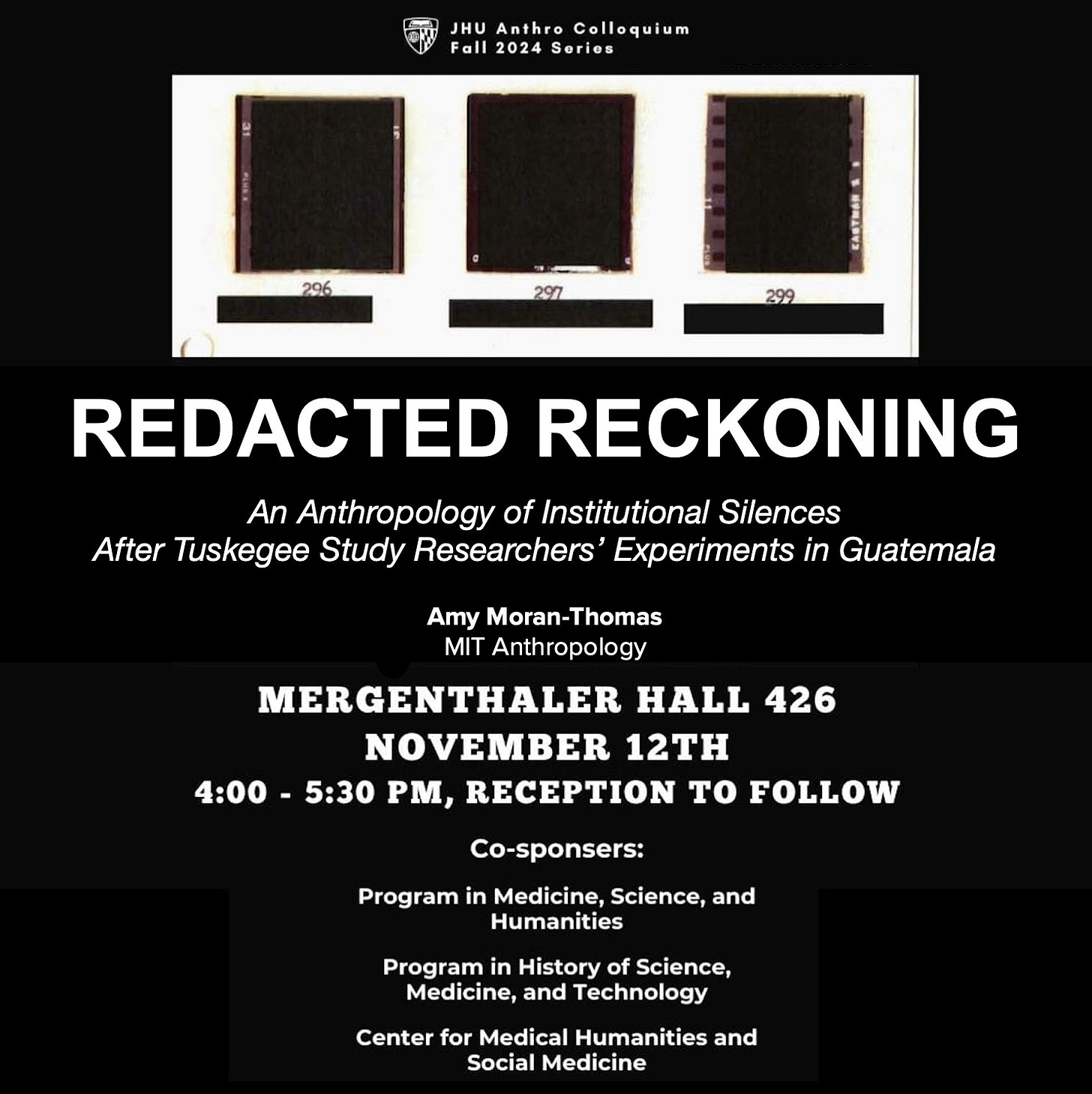

Join us! On November 12, 2024, MIT Anthropologist Dr. Amy Moran-Thomas will present her work on the role of Johns Hopkins in entwined experiments in Guatemala and Baltimore: “‘Redacted Reckoning’: An Anthropology of Institutional Silences After Tuskegee Study Researchers’ Experiments in Guatemala.” November 12, 2024. Mergenthaler Hall 421. 4:— to 5:30 pm eastern time.

“Memorial to the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore.” Baltimore City. Baltimore City Archives (City Council.) Administrative Files. 1850. BRG16-1-91, Box 87. Baltimore City Archives.

Hilary J. Moss, Schooling Citizens: The Struggle for African American Education in Antebellum America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.) For more on Baltimores’ early Black-led schools, see Lawrence Jackson, “Baltimore,” chapter one in Michaël Roy, ed., Frederick Douglass in Context (Cambridge University Press, 2021): 9-20.

Hilary J. Moss, Schooling Citizens: The Struggle for African American Education in Antebellum America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.)