Church and State in Baltimore City

An 1850 Petition Included Religious Leaders Concerned With Schools for Black Children

For this post, Matthew Palmer teamed up with Dr. Monica Blair, formerly of Hopkins Retrospective, to take a closer look at the religious leaders who signed the 1850 “Memorial to the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore.” Johns Hopkins was not himself a religious leader, but this perspective on the petition reveals how, when it came to the schooling of Black children, he shared the view of men who led the city’s Protestant institutions. Among Baltimore’s religious leaders, no consensus existed about how to approach Black education. Some advocated for schooling that prepared Black children for “humble stations in the community.” Others operated schools that provided a more ambitious “English education.”

Several of the men who signed the 1850 petition, “Memorial to the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore,” were active in the city’s religious and educational institutions. They called upon Baltimore officials to act on a request from Black Baltimoreans who had demanded establishment of public schools for their children. The record showed that during the preceding decades, Maryland and Baltimore City had declined to provide schooling for Black children; some religious institutions had stepped in to fill that need. Among the signatories to the 1850 petition were men with ties to those institutions, who endorsed a call for publicly-funded schools that would provide basic education to young Black people in Baltimore City.

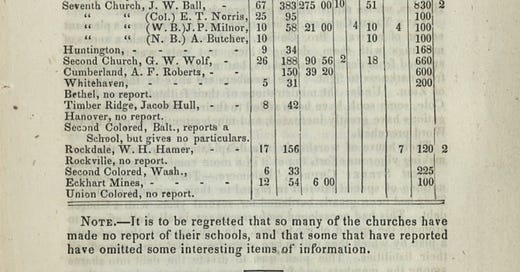

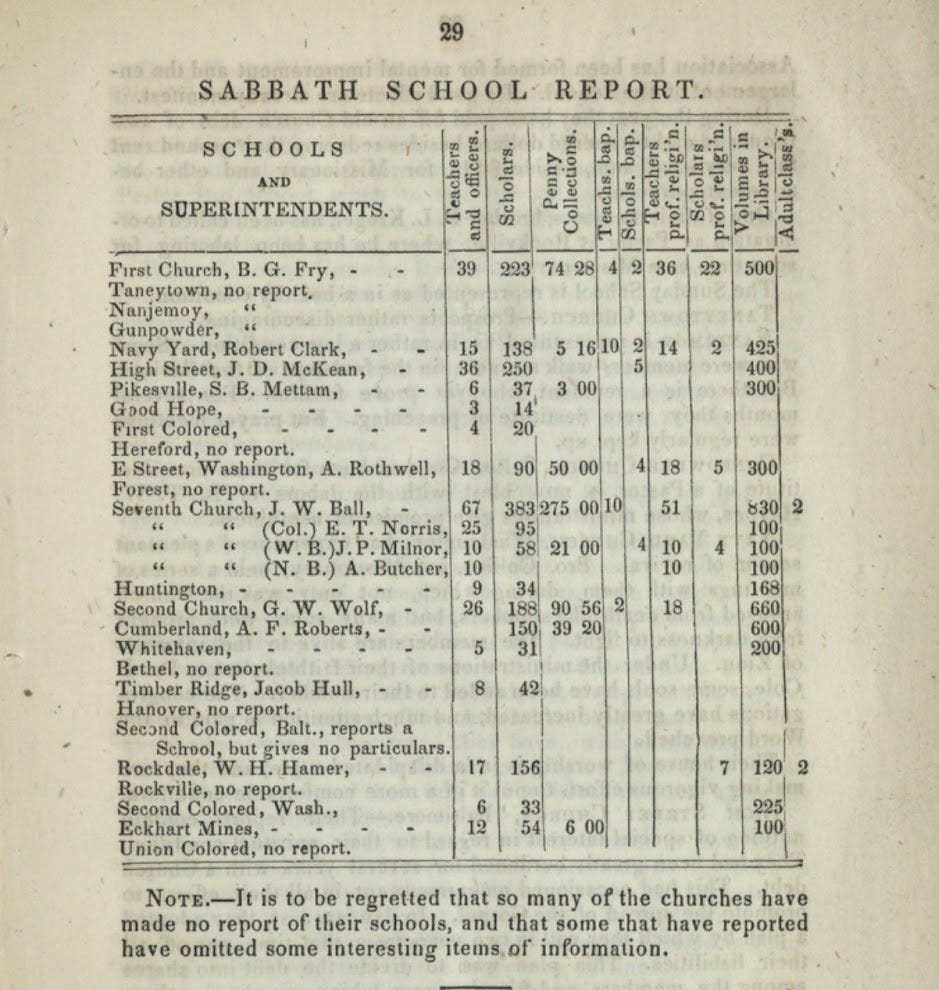

A select group of clergymen, all associated with Protestant denominations, signed the petition. Generally, the 19th-century common school movement, which advocated for free state-supported education for American children, was largely led by Protestant school reformers. We were not surprised then to discover men with similar profiles among signers of the 1850 petition.1 The Reverend Franklin Wilson, a Baptist clergyman, was executive director of the Maryland Baptist Union Association which funded multiple Sabbath schools for free Black children in antebellum Maryland.2 John G. Morris, a Lutheran minister, later became the first librarian of the George Peabody Library.3 Signatories Rev. Isaac Cook, a Methodist, Rev. Jonathan Morris of the First English Lutheran Church, and Rev. Thomas Atkinson of St. Peter’s Protestant Episcopal Church served together on a committee of the Maryland State Bible Society, an organization that promoted reading of the Bible.4

Rev. Thomas Atkinson stands out from his peers; Atkinson was a minister and an enslaver. As reported on the 1850 census for Baltimore City, he held four enslaved people in his household.5 Later recollections of Atkinson noted his support for slavery. In 1909, Bishop Joshua Blount Cheshire of North Carolina recalled that in 1846, when Atkinson was called to become the Bishop of Indiana, he shared his opinion on the subject of slavery. Atkinson, Cheshire reported, recognized the “disadvantages and evils of slavery,” yet also thought that abolition in the South was “impractical” and only manumitted enslaved people if they desired to migrate North.6 Atkinson echoed the perspective of the many Maryland colonizationists who viewed manumission as one step toward excising Black Marylanders from the state’s social and political future.

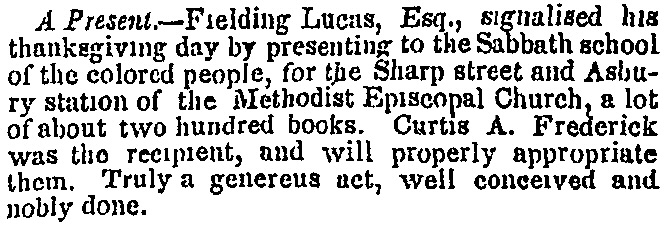

Clergy were not alone in promoting Black schooling. Religious lay leaders also made their reputations, in part, by promoting Black education. Petition signer Fielding Lucas, a 69-year-old bookseller, “signalized his thanksgiving day by giving to the Sabbath School of the colored people, for the Sharp street and Asbury station of the Methodist Episcopal Church, a lot of about 200 books.”7

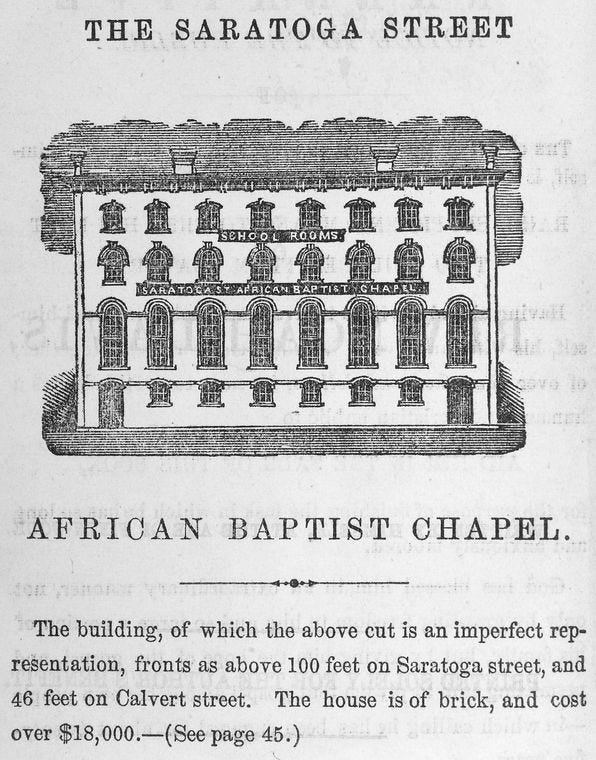

Some signatories, such as William Crane, had long been involved with Black schooling. Upon moving to the city from Virginia in 1835, Crane worked as a leather dealer while also developing ties to Baltimore’s Black Baptist community. In his memoir, A Narrative of the Life of Rev. Noah Davis, A Colored Man, Davis recounted that in 1853 Crane purchased a plot of land which permitted Davis’s Second Baptist congregation to erect a church.8 It grew into a place that mixed religious and academic education: “A church or place of meeting for colored people, and for schools for children of the same race.”9 The alliance between Crane and Davis eventually grew uneasy; Crane never transferred the sanctuary’s title to Davis’s congregation though the group was liable for the construction debt.10 They lost the building which became, in 1865, home to a precursor to today’s Bowie State University, opened there by the Baltimore Association for the Moral and Educational Improvement of Colored People.11

The 1850 petition also reflects some notable absences. Catholic clergy were not among the religious leaders who signed the petition, though we cannot say whether or not they were encouraged to do so.12 Baltimore’s Black Catholic religious leaders were not signatories to the petition, even as among them were those with long-standing commitments to schooling for Black children. Mother Mary Elizabeth Lange, head of the Oblate Sisters of Providence, had operated the Oblate School for Colored Girls (later renamed Saint Frances School for Colored Girls) since 1828. Lange’s school provided a curriculum that included by 1834 “English, French, Cyphering and Writing, Sewing in all its branches, Embroidery, Washing and Ironing,” along with music instruction. By 1853, geography was added while washing and ironing were eliminated. By 1859, girls at the Oblate school studied catechism, reading, history, geography, arithmetic, and writing. This course of study was intended, explains historian Diane Batts Morrow, to challenge “white society’s efforts to circumscribe black life.”13

With the 1850 petition, signatories advocated for Black education from their positions as religious leaders and lay education activists. Their aims were limited. The 1850 petition called for schooling that would prepare young Black Baltimoreans to fulfill “humble stations in the community,” presumably as laborers and domestic servants. This vision contrasts with that which guided the girls’ school operated by the Oblate Sisters of Providence. Their “English education” approach aimed to set Black children on par with their elite white counterparts. Overall, the petition reveals how in Baltimore distinct and even competing ideas about schooling Black children were on the table in 1850.

In observance of the upcoming holiday, the Hard Histories Substack will take a break. We will see you in early December with a closer look at the slaveholders who signed the 1850 petition.

– Matthew Palmer & Dr. Monica Kristin Blair, former Historian & Education Coordinator for Hopkins Retrospective and current Policy Analyst for the Amalgamated Transit Union.

Exciting News!

Former Hard Histories at Hopkins Lab Member Dr. Emma Katherine Bilski has launched a walking tour company – FULL STORY BALTIMORE. Dr. Bilski, our followers will remember, developed a tour themed on the Johns Hopkins Hospital Colored Orphan Asylum for the Lab: “Seeing the Girls’ City.” Dr. Bilski explains: “Our mission was born out of a movement to confront the more difficult and unpleasant parts of our history and to build something constructive from them. This nationwide (and international) movement has deep roots in Maryland and Baltimore, and a wide expression in our local cultural institutions. Baltimoreans have demonstrated their investment in knocking white supremacists down off of their pedestals—and elevating the stories of marginalized people in the past. Full Story Baltimore brings that approach to our walking tours.”

Best wishes for this exciting venture, Dr. Bilski!

Carl F. Kaestle, Pillars of the Republic: Common Schools and American Society, 1780-1860 (Hill and Wang, 1983).

Minutes of the Seventeenth Meeting of the Maryland Baptist Union Association (Baltimore: Innes & Co, 1852).

The diary of John G. Morris, penned during his time as the Librarian of the George Peabody Library, is held by the Johns Hopkins University Libraries. George Peabody Library Records. RG-03-17.

“Other 6,” The Sun (Baltimore, MD), April 7, 1849. Isaac P. Cook would later author a pamphlet on schooling in Baltimore: Early History of Methodist Sabbath Schools, in Baltimore City and Vicinity (Baltimore: Henry F. Cook, 1877).

Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, Baltimore, Maryland, Slave Schedules, Baltimore City Ward 13, p. 577, National Archives and Records Administration.

Marshall de Lancey Haywood, Lives of the Bishops of North Carolina from the Establishment of the Episcopate in That State Down to the Division of the Diocese (Raleigh: Alfred Williams & Company, 1910): 147.

“Local Matters: A Present,” The Sun (Baltimore, MD), November 25, 1848.

Noah Davis. A Narrative of the life of Rev. Noah Davis, a Colored Man (Baltimore: J. F. Weishampel, Jr, 1859), 44.

Martha S. Jones, Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018): 87.

“Bowie State University: Origin & Functions,” Maryland Manual On-Line: A Guide to Maryland & its Government, July 26, 2024. Richard P. Fuke, “The Baltimore Association for the Moral and Educational Improvement of the Colored People, 1864-1870,” Maryland Historical Magazine 66, no. 4 (November 1979): 569-86.

Some white Catholics in the 19th century opposed mandatory public education because they associated common schools with Protestantism, and they preferred to send their children to private Catholic parish schools. On Black Catholic education in Baltimore see Robert N.Gross, Public vs. Private: The Early History of School Choice in America (Oxford University Press, 2018) and James W. Fraser, Between Church and State: Religion and Public Education in a Multicultural America, Second Edition (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

Diane Batts Morrow, Persons of Color and Religious at the Same Time: The Oblate Sisters of Providence, 1828-1860 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002): 88-89, 180-81, 218-19. For a listen, try Stacia Brown, “Don’t Start Nuns, Won’t Be None,” The Rise of Charm City, WEAA 88.9 and AIR’s Localore: Finding America Project.