Seeing Baltimore's Slave Trade

Photographer Amy Davis searched for Baltimore's past and revealed its presence

We might cringe, furrow our brows, and avert our gazes from the homeless encampment. Or we might pause to ask a question about how the sight of human beings huddled in cardboard boxes is a sign of the past. — Martha S. Jones, “First the Streets, Then the Archives.”

Recently, we wrote about Baltimore Sun readers calling for an Inner Harbor redevelopment to include recognition of the part that the city’s port played in the slave trade. We’ve also featured the work of historian Dr. Jennie Williams, who documented how a brutal commerce in human beings operated between Baltimore and New Orleans.

Last week, Sun photographer Amy Davis documented her own search for the sites (and sights) of Baltimore’s slave trading past, from slave pens to the city jail and an auction site at the old Center Market. “Seeing the Unseen” permits us to do just that — get beneath centuries of redevelopment and decay to glimpse the scars that slavery left on Baltimore City.

Davis’s images lend a poignancy to her subject, asking us to consider how the past surfaces in our present through what scholar Joseph Roach termed surrogation. Roach explains how we can more astutely read our present-day cityscape for signs of the unspeakable, inexpressible past resurfaces.1

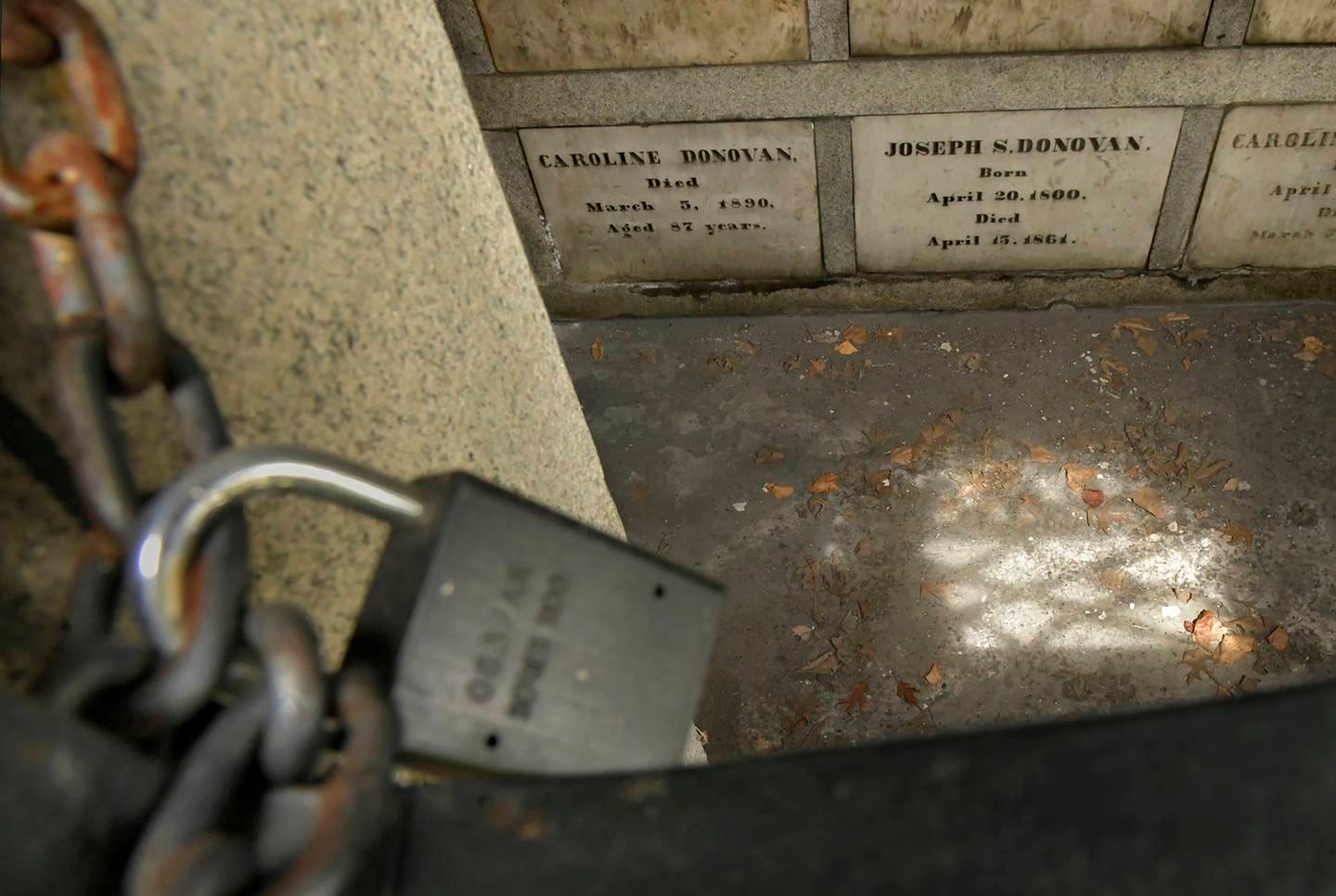

Notice, for example, how the Green Mount Cemetery mausoleum of slave trader Joseph S. Donovan is secured with a lock and chain, a detail that reminds us how Donovan used much the same technology when holding Black Americans captive in the jail behind his home at Eutaw and Camden streets.

Trader Austin Woolfolk was based on the north side of West Pratt Street, where a slave jail was located out back. Davis shows us a small park that now occupies the site and the tents of unhoused Baltimoreans set up there. The devaluation of human lives has a long history in our city and today’s tents remind us of yesterday’s jail cells. Roach suggests they are part of the same story.2

Johns Hopkins University has its own ties to this history. Dr. Jennie Williams explained to the Sun in 2018: “The first endowed chair at Johns Hopkins was established in 1889 by Caroline Donovan, for whom the “Caroline Donovan Professorship in English Literature” is named. She is described as having been a prominent Baltimore philanthropist by the university’s own materials. But that description conceals more than it reveals: Caroline Donovan was also the wife of Joseph Donovan, one of the largest slave traders in the state’s history.” Poet and writer Shelley Puhak told this story back in 2015 in her piece “A Tale of Complicity in the City of Freddie Gray” posted at The Weeklings.

Today, our university website lauds Mrs. Donovan’s gift but does not address its connection to Baltimore’s slave trading past. The most recent holder of the Donovan Professorship retired twenty-plus years ago and perhaps this is the detail to which Joseph Roach would advise us to attend to as we aim to understand how slavery and its legacies still shape the university. With the retirement of the Donovan Professorship’s holder, did the university also retire this tie to the slave-trading past? Is that reckoning? Is it reckoning enough?

Joseph Roach, Cities of the Dead: Circum-Atlantic Performance (New York: Columbia University Press, 1996.)

Martha S. Jones, “First the Streets, Then the Archives,” American Journal of Legal History, 56, no. 1 (March 2016) 92–96.