The Remembrance

The Johns Hopkins Hospital Colored Orphan Asylum and the Girls Who Were Forgotten

When introduced to the Johns Hopkins Hospital Colored Orphan Asylum (JHH COA) at the beginning of the Spring 2023 semester, I immediately found myself with many questions about the children who lived in this asylum, their identities, and their experiences. My final project for the Hard Histories Spring 2023 Research Lab, titled “The Remembrance,” focused specifically on the children—mostly girls, and a few boys in the early years of the institution—residing in the JHH COA.

They were provided with food and housing, medical care, a basic education, Christian religious guidance, and training in domestic service, which would enable them to pursue what Mr. Johns Hopkins described in his will as “respectable employment.”1 We learned early on in our research that the “respectable employment” for these girls was understood by asylum leadership to mean working in domestic service for white families. Research in the JHH COA records—at the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives—and United States Census records allowed us to recover the names and identities of the children. Other external resources, such as the Ancestry record library, served as an aid in discovering unique stories of the girls beyond the census’ classification of them as “orphans” or “inmates.”

The objective of my research was to uncover and share information that might enable surviving family members of these girls to gain a deeper understanding of their loved one’s experiences, while also fostering greater empathy among current and future generations outside of the family. But I soon ran into a challenge: the ethical considerations of confidentiality versus publicizing identities of people marginalized by these “hard histories,” which we discussed in the webinar Hard Histories: Exploring Medical Archives on April 5, 2023, and in a previous Substack post.

Before taking part in that webinar conversation, I had heard multiple perspectives on the confidentiality issue. One perspective, for example, stressed the importance of remembering and honoring the individuals who endured hardships in institutions like the JHH COA; and another acknowledged that publishing their names carelessly could be exploitative and disrespectful. Through discussions (both during and beyond the webinar) with Dr. Heather Cooper, Dr. Ayah Nuriddin, and my fellow classmates Matt and Emma, I gained a new perspective on how to approach these ethical challenges. It led me to the decision that these names should be shared and not anonymized, although with great caution and respect for the girls as well as their descendants. I wanted to make the names of these children easily accessible to any interested family members, and to encourage them to explore this part of their family’s story. After years of their stories being hidden, I felt this approach would be the best way to honor the memory of these girls.2

Over the course of this project, I realized that the names we uncovered are a fundamental starting point for delving deeper into the legacies of the JHH COA. From my research, I was able to craft a preliminary narrative of Minetta W., one of the girls who lived in the asylum:

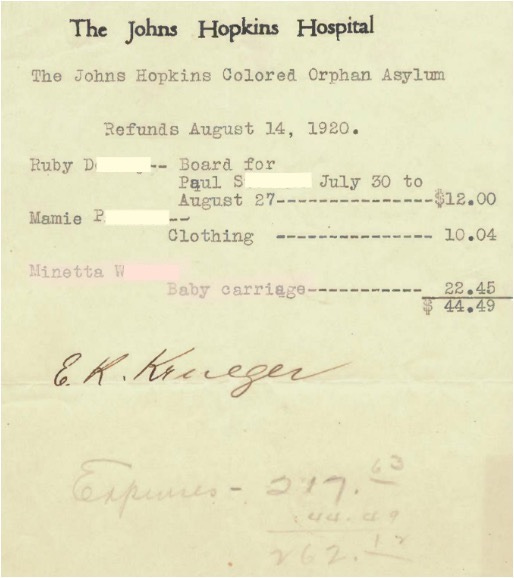

My research began with the 1910 US Census, where Minetta was classified as an “inmate” of the JHH COA at the age of 10.3 However, it was not until I stumbled upon post-closure refund receipts from 1919-1921 (after the asylum had shut down, but was still charged with caring for the girls who remained) that I discovered something particularly compelling. Receipts for the expenses for a baby—her baby—shed light on a previously unknown aspect of Minetta’s life. This prompted me to dive deeper into the Annual Reports of the Johns Hopkins Hospital Colored Orphan Asylum, which revealed that two of the girls had borne children in 1920.4 Furthermore, in 1921, there was a report of a girl—a mother at the age of 23, who was described as “mentally deficient”—who kept her baby for a year while working before the child was boarded in a “properly supervised home.”5 There is no explicit indication that these reports referred to Minetta, but the chronology gives the impression that they did. While the 1920 census showed Minetta as a servant in a Baltimore household, by the 1930 census, she had relocated to Manhattan, New York.6 Accompanying her was Blondine W., Minetta’s sister, but there was no mention of baby Alice. Both sisters worked as servants for private families, although it remains unclear whether they worked for the same family. In the 1940 census, Blondine was noted as lodging with a Black man in New York, but Minetta’s whereabouts at the time are unknown.7

Despite many questions about Minetta and baby Alice remaining unanswered, their story demonstrates that each girl at the JHH COA had their own unique experience. In my opinion, the main takeaway of my final research project is that these girls should not be lumped together as a single entity, “the orphans” or “the inmates.” I sincerely hope that the information uncovered in this project will serve as foundational knowledge for historians, researchers, and family members interested in learning more about the girls at this forgotten institution. When the time comes, I encourage other historians and genealogists to go forth and utilize this information and continue to uncover the stories of these individuals who have been ignored for far too long. Making these names accessible to the public, I hope, will honor their memory and bring attention to the existence of this Orphan Asylum, while also providing an avenue for further research.8

The next step is for the present-day Johns Hopkins institution to acknowledge the JHH COA as part of its history, permanently memorialize the girls, and honor them on an institution-wide level.

Kamal Kaur, KSAS BA ‘25

Emma Katherine Bilski, Editor

Johns Hopkins, Last Will and Testament of Johns Hopkins (1873, no publication information given), 14.

Editor’s note: This fall of 2023, Hard Histories at Hopkins will work in collaboration with descendants when possible to make Kamal’s findings fully available. As many of our readers will understand, these names and identities are sensitive information, and we appreciate your patience in this regard. —EKB

U.S. Census Bureau, "Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910—Population: Baltimore City, Maryland,” Ancestry Library.com, page 8a, accessed May 8, 2023.

Thirty-First Report of the Superintendent of The Johns Hopkins Hospital, 1920, page 79, Records of the Johns Hopkins Hospital Colored Orphan Asylum, Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

Thirty-Second Report of the Superintendent of The Johns Hopkins Hospital, 1920, page 83, Records of the Johns Hopkins Hospital Colored Orphan Asylum, Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

U.S. Census Bureau, "Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930—Population: Manhattan, New York, New York,” Ancestry Library.com, page 7b, accessed May 8, 2023.

U.S. Census Bureau, "Sixteenth Census of the United States: 1940—Population: New York, New York, New York,” Ancestry Library.com, page 3a, accessed May 8, 2023.

See footnote 2 above.