In August, Hard Histories at Hopkins veteran Matthew Palmer returned to the Lab and took on a special assignment. A new document had surfaced — the 1850 “Memorial to the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore” — and Matt brought to bear their research expertise to teach us more about this dimension of Mr. Johns Hopkins’ world. Recovering the biographies of the 120 signatories to the petition permitted Matt to better see how the city’s elite men, including Mr. Hopkins, variously positioned themselves between slaveholding, negotiating with a growing free Black community, and planning the future of public education in Baltimore.

As I researched the 1850 petition to the Baltimore Mayor and City Council, I was surprised to discover how many merchants contributed their signatures to a call for the establishment of schools for Black children. I set out to discover how interconnected the elite men in Baltimore were in the mid-nineteenth century and learned that many of the signatories to the petition knew each other through business dealings prior to 1850. Following the lead of recent research into merchant and philanthropist George Peabody, I also examined the signatories’ ties to slavery both before and at the time they signed the 1850 petition. Among those men were Johns Hopkins, Jacob G. Davies, and Frederick W. Brune.1

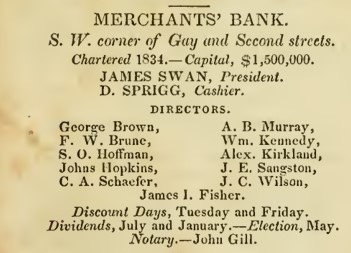

In the mid-nineteenth century, Baltimore’s merchant class was made up of men engaged in varied economic enterprises as bankers, rail road directors, and enslavers.2 Johns Hopkins was wealthy and budding philanthropist whose economic activities reflected the diversity of Baltimore’s merchant class. His banking interests linked Mr. Hopkins to other petition signatories. An 1845 Baltimore city directory, for example, identifies Mr. Hopkins as a director of the Merchants’ Bank alongside petition signers Frederick W. Brune, James I. Fisher, George Brown, and Alexander Kirkland.3 Railroad investments also linked Mr. Hopkins to other petitioners. In 1827, prominent men had met to discuss the construction of a railroad line in Baltimore, with a committee later advocating for a line connecting Baltimore with the Ohio River.4 By the 1840s, Mr. Hopkins was not only a bank investor, he associated with other petition signers through directorship of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. At an 1847 B&O shareholder meeting in Pittsburgh, both Johns Hopkins and signatory Jacob G Davies were appointed to a committee. With them was lawyer and signatory John Glenn.5

In Mr. Hopkins’ business circles, signing a petition that endorsed public schools for Black children was not inconsistent with slaveholding. Some merchants simultaneously supported establishing such schools while also holding enslaved people. As explained in Dr. Martha Jones’s 2020 special report, in the same year that Mr. Hopkins signed the 1850 petition, the U.S. census for Baltimore reported that he held four enslaved people in his household. He was typical of Baltimore slaveholders. Mr. Hopkins did not operate a large plantation, nor did he deploy an extensive workforce. Instead, he held a smaller number of enslaved people who likely made up a domestic staff.6 Census records indicate that signatory and Merchant’s Bank director Frederick W. Brune had held two enslaved people in 1820, though by 1850 Brune was no longer reported holding slaves.7 Instead, in that year his household included four free Black women, presumably domestic workers.8 Signatory Alexander Kirkland held one enslaved person in the year 1850.9 Among the petitioners connected to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, the case of John Glenn is somewhat difficult to gauge. Census records show two enslavers named John Glenn living in Glenn’s neighborhood, Baltimore’s 13th Ward, in 1850.10

Signatory Jacob G. Davies was not only a prominent merchant, he was an influential political figure, serving as the mayor of Baltimore from 1844-48.11 Davies' position as Mayor often had him rubbing shoulders with signers of the 1850 petition during social events. In 1848, for example, several petition signers attended an event at Monument Square to celebrate European republicanism.12 The occasion lauded human liberty, and still several attendees including Johns Hopkins, John Glenn, and William H. Marriott were also enslavers. Davies himself, as reported on the census of 1840, had held three enslaved people while also employing two free people of color.13 There is no evidence that Davies remained an active enslaver in 1850, the year in which he signed the school petition. Marriott on the other hand appears to have held enslaved people, though the record is not wholly clear. Was the signatory to the 1850 petition the William H. Marriott with a Howard County plantation where he reportedly held ten enslaved people in 1850? Or was Marriott the Baltimore City resident who held three enslaved people in his home?14

While many of these merchant-signatories were born in Maryland, several were born in Europe and immigrated to the United States for financial opportunity. In 1799, Frederick W. Brune left the city of Bremen, in today’s Germany, and established himself as a merchant in Baltimore. He, like other immigrant merchants, helped foster international business connections between Maryland, Europe, and Latin America. Brune himself worked as an agent for the underwriters in Bremen.15 Fellow Bremen immigrant and signatory J.F. Strohm strengthened this international connection, serving as Foreign Consul to Venezuela for Baltimore City.16 When I began this research, I wondered if immigrants also became enslavers after arriving in the United States. As noted above, Frederick Brune was an enslaver by 1820 and other immigrant and signers of the 1850 petition did as well, including the Ireland-born conveyancer George R. Cinnamond who reportedly held two enslaved people in 1850.17

Much like the growing industries of railroads and banking, the 1850 petition brought together a diverse group of men from Baltimore’s merchant class. Both native-born and immigrant men participated in a broad range of economic activities and assumed important positions in the city’s social and political life. Some of these same men also did business with or were themselves enslavers. A close look at their commercial dealings and the composition of their households reveals how, in Baltimore, philanthropy and capital development were companions to slaveholding and the promotion of schools for Black children.

Merchants were not the only signatories to the petition who had ties to one another and to the institution of slavery. Next week, Dr. Monica Blair and I will share some about the religious leaders who were also signatories to the 1850 petition.

— Matthew Palmer

These findings resonate with those arrived at in a 2023 article, “George Peabody and Slavery.” There, Historian Anne-Marie Angelo explored the ties between George Peabody, founder of today’s Johns Hopkins Peabody Conservatory, and slavery.

Matthew A. Crenson, Baltimore, A Political History (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017), 163.

John Murphy, The Baltimore directory for 1845: containing the names of the inhabitants, their places of business and dwelling houses, the City register, directions for finding the streets, lanes, alleys, wharves, &c. with much other useful information (Baltimore, MD: John Murphy, 1845), 160.

David Schley, Steam City: Railroads, Urban Space, and Corporate Capitalism in Nineteenth-Century Baltimore (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020).

“Meeting of the Stockholders of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad,” The Sun, (Baltimore, MD), Mar. 23, 1847

T. Stephen Whitman, The Price of Freedom: Slavery and Freedom in Baltimore and Early National Maryland (New York: Routledge, 1999) and Christopher Phillips, Freedom’s Port: The African American Community of Baltimore, 1790-1860 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997).

Fourth Census of the United States, 1820, Baltimore, Maryland, Baltimore Ward 6, p. 317, National Archives and Records Administration (hereinafter NARA).

Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, Baltimore, Maryland, Population Schedules, Baltimore City Ward 10, p. 68, NARA.

Seventh Census of the United States, 1850; Baltimore, Maryland, Slave Schedules, Baltimore City Ward 14, p. 175, NARA. Among other directors of the Merchant’s Bank, S. Owing Hoffman was reported as holding two enslaved people, a woman aged 60 and a man aged 35, in his household (Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, Baltimore, Maryland, Slave Schedules, Baltimore City Ward 11, p. 210, NARA) as was Daniel Sprigg who held two enslaved people in his household as reported on the 1860 census (Eighth Census of the United States, 1860, Baltimore, Maryland, Slave Schedule, Baltimore City Ward 20, p. 2, NARA.)

Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, Baltimore, Maryland, Slave Schedules, Baltimore City Ward 13, p. [597] and 599, NARA.

“Jacob G. Davies (1796-1857),” Archives of Maryland (Biographical Series), Maryland State Archives, accessed October 26, 2024,

The Mass Meeting of the People of Baltimore, in Honor of European Republicanism,” The Sun, (Baltimore, MD), May 4, 1848.

Sixth Census of the United States, 1840, Baltimore, Maryland, Baltimore Ward 7, Baltimore, Maryland, p. 23-24, NARA.

Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, Anne Arundel County, Maryland, Slave Schedule, Howard District, p. [233.] Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, Baltimore, Maryland, Slave Schedules, Baltimore City Ward 13, p. 397, NARA.

R.J Matchett, Matchett's Baltimore Director, for 1849 '50; Containing the Names, Dwellings and Occupations of the Householders (Baltimore, MD: R.J Matchett, 1849), 11.

Ibid.,11.

Seventh Census of the United States, 1850, Baltimore, Maryland, Slave Schedules, Baltimore City Ward 10, p. 579, NARA.