Mr. Hopkins and the Schooling of Black Children

An 1850 Petition Suggests That His Interests in Education Were Varied and Sometimes Divergent

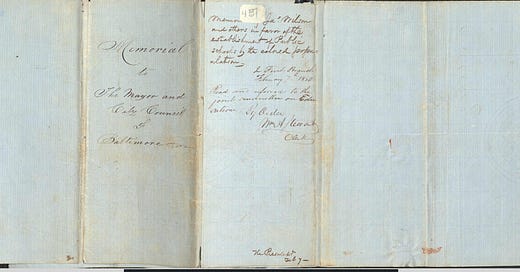

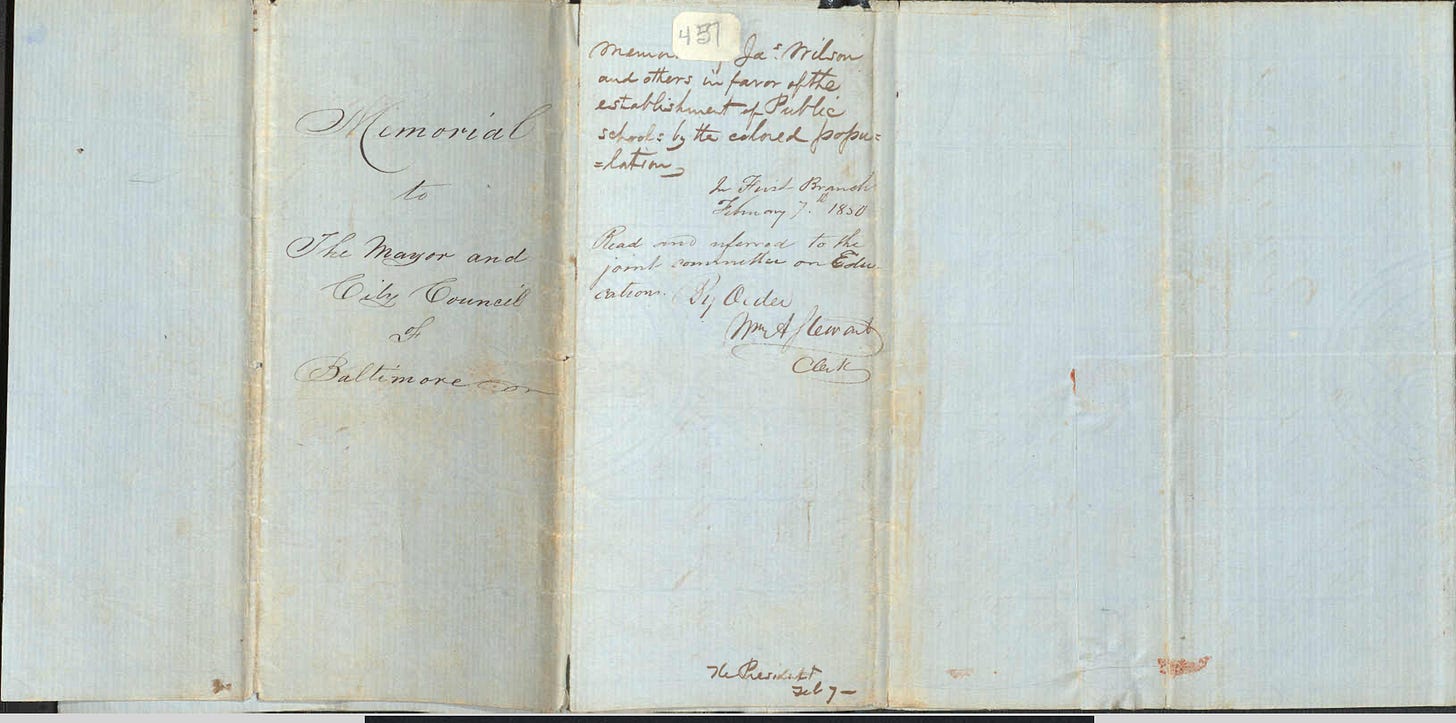

Through the efforts of the Baltimore City Archives, we are pleased to be able to share here high resolution images of the 1850 “Memorial to the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore.” Have a closer look at the full text of the petition and the names of its signatories. Thank you to BCA and its staff for supporting the researchers from Hopkins Retrospective and Hard Histories at Hopkins.

Our series on the 1850 “Memorial to the Mayor and City Council of Baltimore” began with an investigation into the text and its signatories, especially looking for new insights into our founder and namesake, Mr. Johns Hopkins. In this post, we sum up some of what we’ve learned.

In 1850, Mr. Hopkins endorsed a petition that encouraged the City of Baltimore to establish public schools for Black children. The petitioners called for such schools to be limited to instruction “in such elements of learning as may prepare them to fill, with usefulness and respectability, those humble stations in the community to which they are confined by the necessities of their condition.” This contrasted to other approaches to Black schooling in Baltimore, such as that of the Oblate Sisters of Providence. By 1853, the Oblate curriculum included English, French, Cyphering and Writing, Sewing in all its branches, Embroidery, Music Instruction, and Geography.1

Mr. Hopkins, when he signed onto the 1850 Memorial, expressed a shared interest in schooling for Black children. He was, in this sense, part of a civic community that organized an appeal to the Mayor and City Council. These men, our research revealed, did not take a shared approach to securing labor for their households. A small number, 14 men, like Mr. Hopkins held enslaved people at home, presumably as domestic workers. A significantly larger number, 39 or 35%, relied instead on free Black laborers at home. Many of these households were shifting their labor arrangements and, like Mr. Hopkins, by 1860 no longer held slaves. Baltimore’s Black workforce had become dominated by free people, not slaves, by then.2

Among the petitioners were men for whom education was among their key civic concerns. For some this included schooling for Black Baltimoreans. We considered that, for Mr. Hopkins, the decision to sign the 1850 Memorial may have marked the start of his own interest in the same questions. Consider, for example, that by 1856 Mr. Hopkins was reported to be among the trustees of the “School for Free-Colored Girls in Washington” headed by Myrtilla Miner. That school grew out of the same concerns that inspired Baltimore’s 1850 petition: The District’s 11,000 free Black residents “excluded by law from schools and destitute of instruction.”3

We also considered the parallels between the 1850 Memorial’s vision for Black education — schooling for humble stations — with the approach later taken up by the Johns Hopkins Hospital Colored Orphan Asylum, a place organized to train Black girls for domestic work. This connection cannot be ascribed to Mr. Hopkins’ doings alone, of course. He provided for the asylum in his will, but its organization and administration were in the hands of hospital trustees and the “lady managers” who oversaw its operations. Still, the continuity is striking: As was true in the 1850s, it was true in the 1870s and beyond: Among Baltimore’s white elite were those who supported education that fixed the status of Black Baltimoreans as assets to white households.4

The 1850 Memorial opens a new window onto Mr. Hopkins, his circle of peers, and his civic concerns. It suggests that his interest in education, including the schooling of young Black people, developed over time. And while many followers know well his interest in elite schooling for young white men, following the path he started along in 1850 suggests that Mr. Hopkins’ interests were both broader and more divergent. Finally, it is worth saying as we did at the outset: when it comes to Mr. Johns Hopkins the historical record remains thin and fragmentary. Many questions we cannot wholly answer. And still, four years into our work at Hard Histories, we are certain that new discoveries are possible.

Tune in after the holiday season when we’ll conclude this series with a closer look at the companion 1850 petition put forward by Black Baltimoreans. Theirs was the initiative that inspired what Mr. Hopkins and his fellow petitioners did next.

— MSJ

P.S. I spent last weekend at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, as part of their annual “Curating Scholarship: A Workshop on the Visual Presentation of Research,” talking about our Wyman Park Building Lawn installation that featured the girls resident in the JHH Colored Orphan Asylum. There, I was alongside artist Mark Dion and learned about his stunning and richly historical installation here at Johns Hopkins, “An Archaeology of Knowledge.” Have a look for yourself!

“School for Free-Colored Girls in Washington,” Washington Union, May 13, 1857, 3. Michael Flusche, “Antislavery and Spiritualism: Myrtilla Miner and Her School,” New-York Historical Society Quarterly 59, no. 2 (April 1975): 43-166.

Rebecca Shillenn, “Footprints from the Past,” Arts & Sciences Magazine, Fall 2023.